No cultural artefact is too lowly or trivial for Ecos analysis. He has analysed the Mad magazines and, with equal fizz-bang, pulpy strip-cartoons such as Camelot 3,000 and The Savage Sword of Conan the Barbarian. This is what Eco does best: applying literary judgement to ephemera.Īs Professor of Semiotics at Bologna University, Eco has decoded the James Bond novels and the Peanuts comics. His conversation swerved giddily from Pre-Raphaelite forgeries to counterfeit Louis Vuitton handbags, from the World Cup to the porn star Marylin Chambers. When I visited him in 1986, he shuffled grumpily round his office, lifting up and slamming down books. But where could Eco go from here? The Name of the Pendulum, perhaps, by Umberto Foucalt? Eco was trapped in his own fame. Reviewing this comic-strip farrago for The Observer, Salman Rushdie confessed: Reader, I hated it. A narrative calamity, then. This time, Denis Wheatley was combined with Hugo, Poe and Eliot. Unfortunately, it was magnificently boring. The Eco Chamber, he calls it.Įcos second novel, Foucaults Pendulum, had the look and feel of an encyclopaedia. Ecos gifted English translator, William Weaver, built an extension on to his Tuscan home with the proceeds. Not since One Hundred Years of Solitude had there been such a consensual success on the book market. It sold five million copies worldwide and was translated into 24 languages. In reality, Ecos medieval whodunnit was up-market Arthur Hailey with frills on. Its baggage of arcane erudition was designed to flatter the average readers intelligence. Ecos freak bestseller, The Name of the Rose, was an artful reworking of Conan Doyle, with the Baker Street sleuth transplanted to fourteenth-century Italy. Switch it on and hey presto! out pours an interesting book.

In go a dash of Mickey Spillane, a pinch of Borges, some diced semiotics.

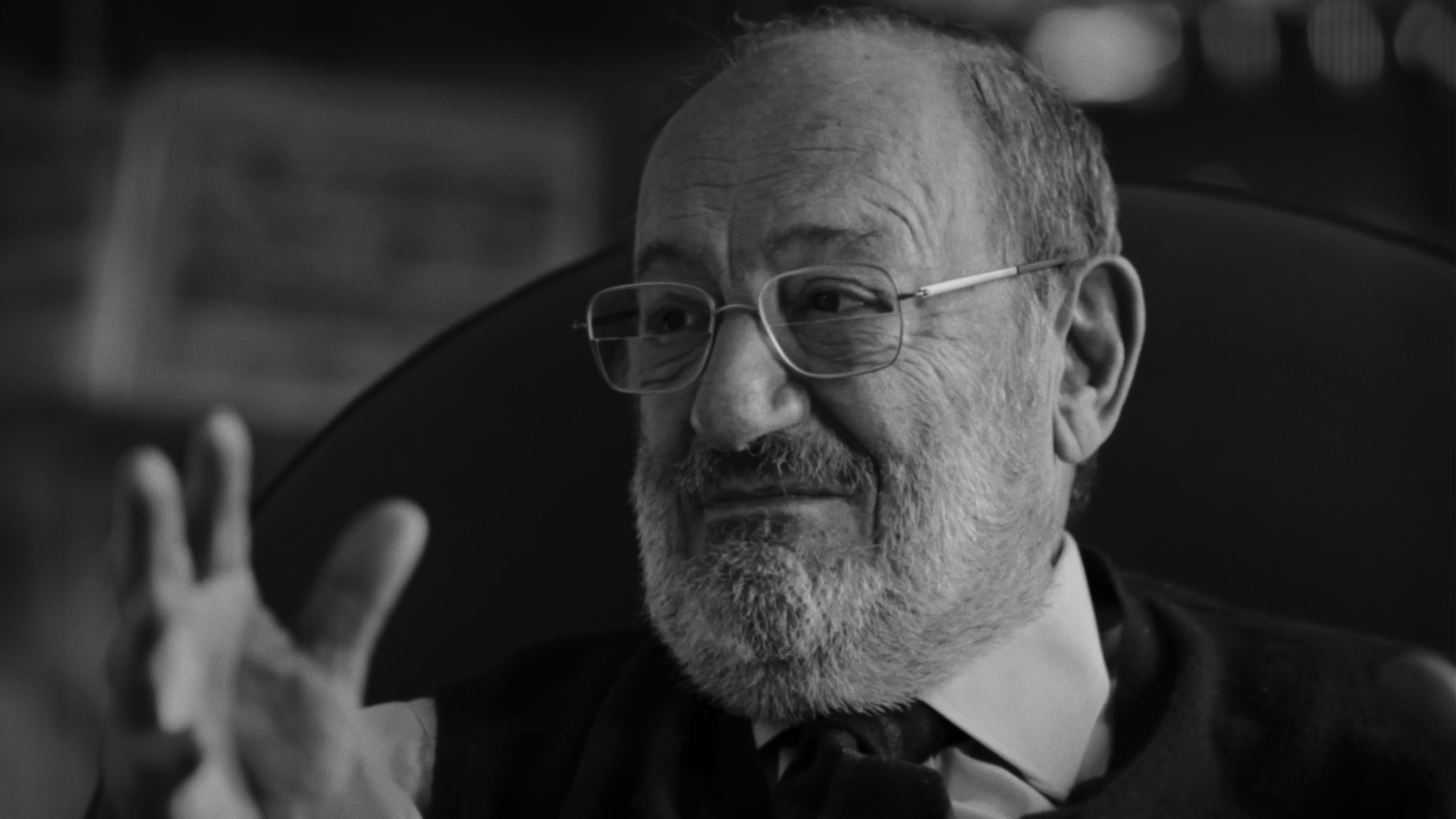

However, his mind works like a kitchen blender. Umberto Eco, now a plump 67, is a man of towering cleverness.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)